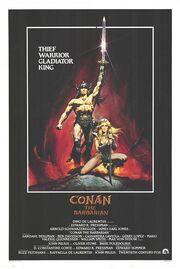

Spoiler alert – this has nothing to do with the 1982 Conan Movie…

Spoiler alert – this has nothing to do with the 1982 Conan Movie…

Yesterday, I went to see a metal worker. I needed some bits made for my garden railway and had spent some hours working on the design I wanted and drawing it up in Visio. It took him about ten minutes to point out all the flaws in my design – not from a functional perspective, but from the manufacturing point of view. But he priced it up anyway, because that’s what I had asked him for. Twenty minutes later, he had worked out two alternative designs that will be cheaper and easier to build, with less wastage and better functionality.

At this point, I should observe that I am a writer, not an engineer.

There are valuable lessons which could be learned from this exercise:

For Tenderers

- When you approach the market, you usually have a clear idea of what you want, and this is dangerous. By specifying your requirements and the current state of your systems (people, processes, IT, whatever) you might get something that is not what you imagined but might be better.

- Be specific about what functionality you actually need, as opposed to what you might merely want.

- Be flexible in your approach to evaluation – if something meets the functional and non-functional requirements but is not “what you thought of”, that should not be reason to exclude it.

For Responders

- It’s important, first and foremost, to give the customer what they asked for.

- It’s equally important to point out better and cheaper ways of achieving the objective, if you have the wit and time to think of them.

- Naturally, it’s better to get involved at the design stage – before the customer goes to market.

What is the riddle of steel? For me it is: “How do you build something that is flexible, but strong?” That goes for proposals and metalwork equally.